Nicola Mason: Decades ago I went into publishing, not just because I love literature, but because I love copyediting. There’s a special pleasure in immersing myself in a writer’s style and syntax, the world of their story, essay, poem, or novel. My enjoyment is especially keen when the material doesn’t just touch me, it informs me. I’d even say I’m most attracted to those works, most interested in those worlds.

Such was the case when I first began reading Michael Downs’s The Strange and True Tale of Horace Wells, Surgeon Dentist—and I’m re-experiencing that enthrallment as I work through the manuscript during the copyediting process. Take, for example, this passage:

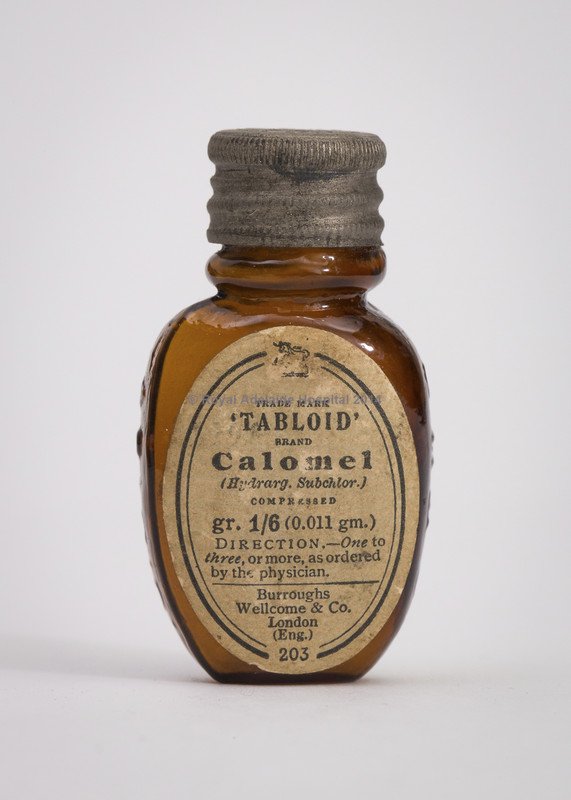

Colton bolted the door, swallowed a gulp of cider, a bite of meat. He could not sit comfortably in that hard-backed chair. He arched his spine, tried twisting a bit to the side, lifted a leg over the arm. The pain would not diminish. No, not pain. The word was too strong, tossed about too easily in this room this night. His back ached. He knew the difference between an ache and a pain. His father knew true pain, what he’d once called a hot curl of ash inside his ear. The man had endured. Attended his fire and his molten iron every day, hammering nails and shoes for horses. Swung his tools even as that worm of pain burrowed and squirmed. No doctor could explain it, nor any minister. Old women made tinctures of root and herb; doctors prescribed calomel. Nothing worked. And here came Papa into Colton’s head, a clear picture, half his face a grimace, probing his ear with a finger or with a swab of cotton on the end of a stick, digging around, trying to kill the pain. Always, every day. His night moans, his sudden whoops at the dinner table as if he’d been bit. How he, a pious man, gave in to the vilest oaths. The skin around his eyes grew sallow from sleeplessness, his nocturnal roaming. Then came the day young Colton found his father in the barn, sprawled in the hay, a red and brown halo where his head lay, his eyes open but his skin cold, a bloody hole where his ear had been, and still in his fist that knife he had used to kill the worm.

A harrowing passage. As a reader, I feel the horror of it. I consider, imagine, recoil from the kinds of pain present in this memory: physical, emotional. As an editor, I catch upon calomel, which, as I fact-check the word, presents me with another form of fascinated horror. Mercury chloride, or calomel, was frequently used in the nineteenth century to treat ailments from pneumonia to venereal disease to . . . teething pain in infants. It is, of course, quite toxic, though doctors at the time considered the merits of this impressively powerful substance to outweigh its detrimental effects. They were wrong. Interesting little-known lit fact: there’s strong speculation that Louisa May Alcott died, not of typhoid, but of mercury poisoning from the treatment prescribed for her illness: high doses of calomel.

This is merely one example of the richness of Downs’s writing, which undergirds feeling with fact, both transporting and teaching the reader over the course of his sweeping narrative.