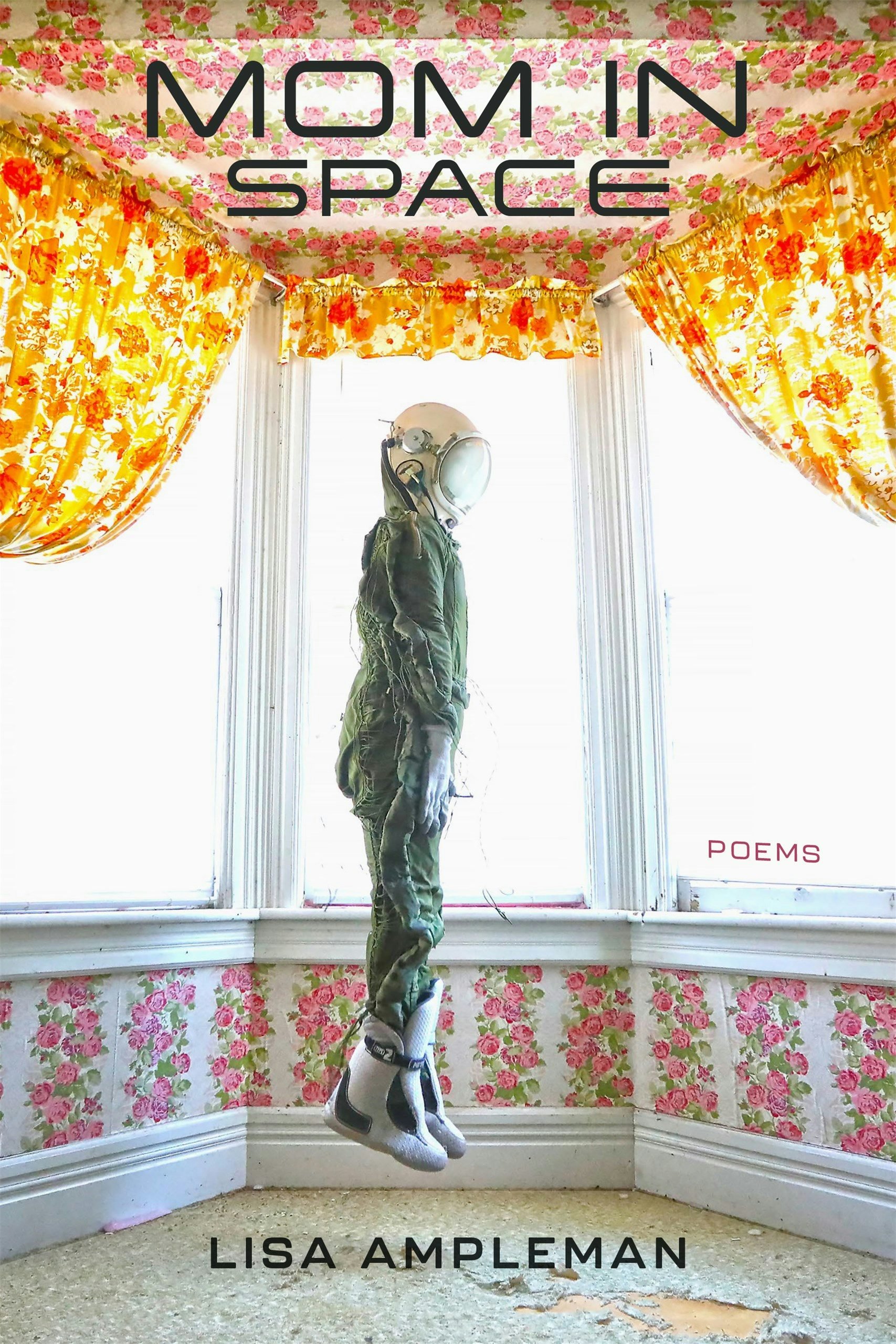

Simon Smith Interviews Poetry Series Editor Lisa Ampleman, Author of MOM IN SPACE

Through her multifaceted roles as the managing editor of The Cincinnati Review and Acre’s poetry series editor, Lisa Ampleman helps to champion the work of emerging and established poets. She is also an accomplished poet in her own right, author of the collections Full Cry (NFSPS Press, 2013), Romances (LSU Press, 2020), and Mom in Space (LSU Press, 2024).

In this staff interview, the first in a series spotlighting the people behind Acre Books, Simon Smith speaks with Ampleman about her editorial perspective, creative process, and the inspirations behind her third full-length book of poems.

Simon Smith

Lisa Ampleman

SS: You’re an editor and poet all rolled up into one. How do you manage these roles? Do you have any advice for those who struggle with revision?

LA: Well, I’ve found that context helps. In my home office, I have a computer and monitor setup on a desk, which is where I do my work as an editor. But I have a green armchair I sit in when I’m spending time with poetry (reading, writing). That’s quite a literal division, but otherwise the two feel like very different parts of the brain at this point of my career. It’s like opening the door to a room full of tools or a room with a blank canvas or painting-in-progress.

For those who struggle with revision: sometimes you need more time so you can see the piece as something separate and malleable; sometimes it helps to get feedback from others and then sit on it for a while before revising; sometimes it helps to go back in right away, if you get excited about a new direction for the piece after feedback; sometimes, I’ve discovered, you just need to live more of your life and come across an experience or image that helps you elevate the piece—that last one is something you can’t make happen, though.

SS: While being an editor is challenging enough in its own right, I can only imagine the complications that arise when adjusting for poetry. After acquiring a poetry manuscript for Acre, what is your process for working with the poet on edits?

LA: In some cases, the books we’ve accepted were complete and needed only copyedits. In others, I’ve given the writer my perspective on their latest draft, in general terms, usually not prescriptively, and let them run with it. Faylita Hicks, for example, would come back with a draft she’d worked on extensively, something leaps and bounds above the already-good previous draft, in a direction I had not even thought to anticipate. She is a dynamo, and she knows how to go with her gut. I’ve encouraged that process with other poets since, when larger scale revisions were needed (which isn’t often): I give some ideas, but the writer does with them what they will; they know the material more deeply than I ever will. In copyediting, on the level of the individual poem, I look for issues of house style, if “&” and “and” appear in the same poem, fact-check names, etc., but I phrase almost all of those as queries for the poet and allow for “poetic license” in the process. I used to think that copyediting had a “right answer” you could get to, like in math, but now I see it’s more like the interpretive act of reading a poem.

SS: Your newest poetry collection, Mom in Space, uses cosmic phenomena to explore aspects of the human experience, society, and other anthropological concepts. What made you chose an astronomical theme? How does this collection speak to the ideas and topics you’re interested in, both as a writer and reader?

LA: In the winter of 2019–2020, the Cincinnati Museum Center had a special exhibit featuring the Apollo 11 command module. I went once in October and again in January, fascinated in particular by the script for a speech Neil Armstrong gave at the museum’s anniversary party twenty-five years ago (I say a little bit about that experience in a lyric essay in the book and in one of the poems). I noted a book in the exhibit’s gift shop about the Apollo program (A Manon the Moon by Andrew Chaikin) and brought it with me to a residency in Florida in February of 2020. The narrative of the program hit me in a way it hadn’t before, and when I got back, I wanted to read about “what happened next”: Skylab, Mir, the Space Shuttle, etc. I had those books at home just as the pandemic lockdowns started, so it was a way to escape, in a way. I don’t have any other logical explanation, but I think there’s a sense of awe also.

I found myself reading about space and writing about (in part) experiences with infertility and miscarriage that sat as great griefs inside me but that I hadn’t fully processed yet. The book also addresses climate change, civil rights, and other social topics through the lens of spaceflight. I’m interested in reading about all of those things, but the alchemy of those coming together excited me as a writer. There were so many things I read while I worked on this book that blew my mind: for example, Nichelle Nichols, who was Lieutenant Uhura on the original Star Trek, was friends with Maya Angelou, worked on a play with James Baldwin, and stayed on the TV show after Martin Luther King, Jr., told her she should, for all those Black viewers who finally saw themselves in a major character. AND Nichols played a major role in a recruitment campaign for the Shuttle program, recruiting the first astronauts of color and women.

SS: What contemporary poets do you admire—perhaps a favorite piece of theirs?

LA: That’s a hard question—the hardest yet; the answer varies from year to year.

One mainstay is Kimberly Johnson, who is amazing and underappreciated for her talent—she has received recognition for her work, but I think she deserves more. I love “Fifteen,” for example, which appeared in The Cincinnati Review (I am, I acknowledge, biased in that choice) and then in Best American Poetry. “Foley Catheter” is devastating, in the right way; that one appeared in the Poem-a-Day series from the Academy of American Poets. All her poems have such rich use of internal rhyme, assonance, and other sonics that wow me.

I’ll also mention Jorie Graham, whose early work in particular has been a favorite of mine for decades; from her latest book, I really loved “Thaw.” Graham is fantastic at a meditative mode that mixes the gaze of a philosopher with mindfulness. I think I wrote during my MFA years about her use of the gerund, -ing, to keep the present moment going syntactically.

To learn more about what poetry inspires Lisa, browse through the catalog or head over to our submissions page to read her description of what she and publisher Nicola Mason look for and love in a manuscript!