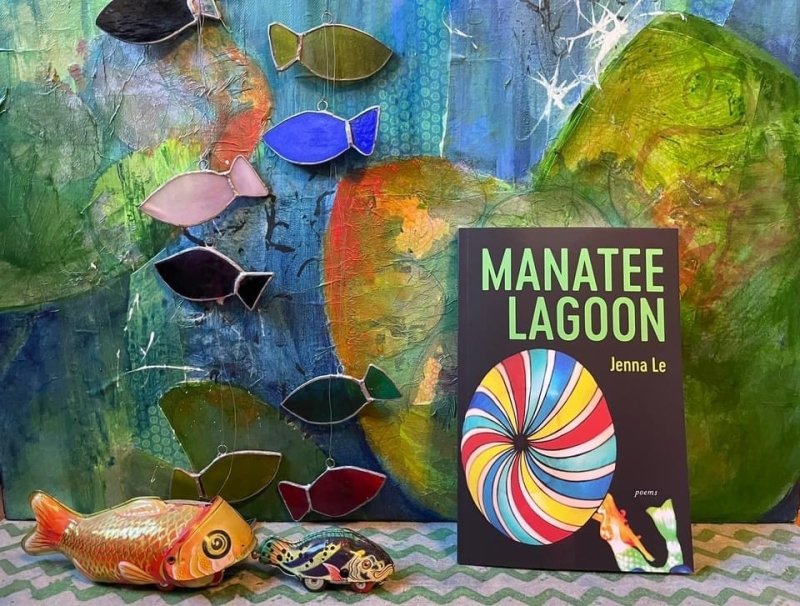

Poetry Editor Lisa Ampleman Interviews Jenna Le, Author of MANATEE LAGOON

LA: Manatee Lagoon is your third published collection. How did your experience of writing and organizing it compare to your other books? Did it feel like a “project” or just writing poems and putting them together?

JL: I naturally have a superstitious temperament, which makes it a bit hard for me to look at life on a big scale. Like, I have a hard time answering questions like, “What will I be doing a year from now?” because who knows what a year from now will look like? I sometimes worry the gods will strike me down for hubris if I make overly concrete plans for next week, much less next year! I’m much more comfortable thinking about life in a “micro” way: focusing on the one poem I’m writing right now, the one line I’m struggling with crafting right now. It’s been that way with all three books I’ve written: the individual poems always came first. But since I also have a naturally obsessive temperament, my obsessions helped unconsciously organize my poems into thematically connected units. This sometimes only became clear after I’d written the individual poems and sat back to look at the notebook as a whole.

LA: Your work exhibits a commitment to forms and formal verse. I’d love to hear more about how that aesthetic developed and how or if it impacts you during the act of writing.

JL: The very first poems I remember reading that gave me a visceral thrill were the rhymed and metered poems you find in classic anthologies: old English murder ballads like “The Twa Sisters,” romantic sonnet sequences like Sidney’s “Astrophil and Stella,” etc. My parents kept the house full of books like that when I was little, so I read all those poems when I was a young kid. I jived with how those poems used elements like rhyme, meter, and refrain to become something more than prose narratives: each was a crafted object you could turn over and over in your palm, which would be breathtakingly beautiful from any angle, gorgeous by virtue of internal symmetry, geometry, repetition, and proportion. Each line needed every other line not just because of what it contributed to the sense and the story, but also because of what it contributed to the form and the music, so you got these stronger covalent bonds between the words.

Poetry Editor: Lisa Ampleman

Author: Jenna Le

Once, when I was little, I excitedly recounted to my mom the story of the murder ballad “The Twa Sisters” — the sibling rivalry, the way the bad sibling gets her comeuppance at the end — and my mom sort of scoffed dismissively at it, like it was just some naive Freudian wish-fulfillment yarn or something. You can scoff at a story, but it’s much harder to scoff at a poem with formal elements: the formal elements become an armor, a scintillating metallic carapace that gives the words durability in both the individual and collective memory, a kind of enhanced legitimacy. If the poets of the long-ago romantic sonnet sequences had just written about their squishy feelings in a prose diary, we wouldn’t give them a second thought now, but the formal elements amplified their voices: choosing to weave in those formal elements was one way of stepping up and asserting that the individual mattered, that the individual was part of this larger tradition and lineage, even if the writer was someone marginalized by society. That angle has just always been baked into my love of poetry.

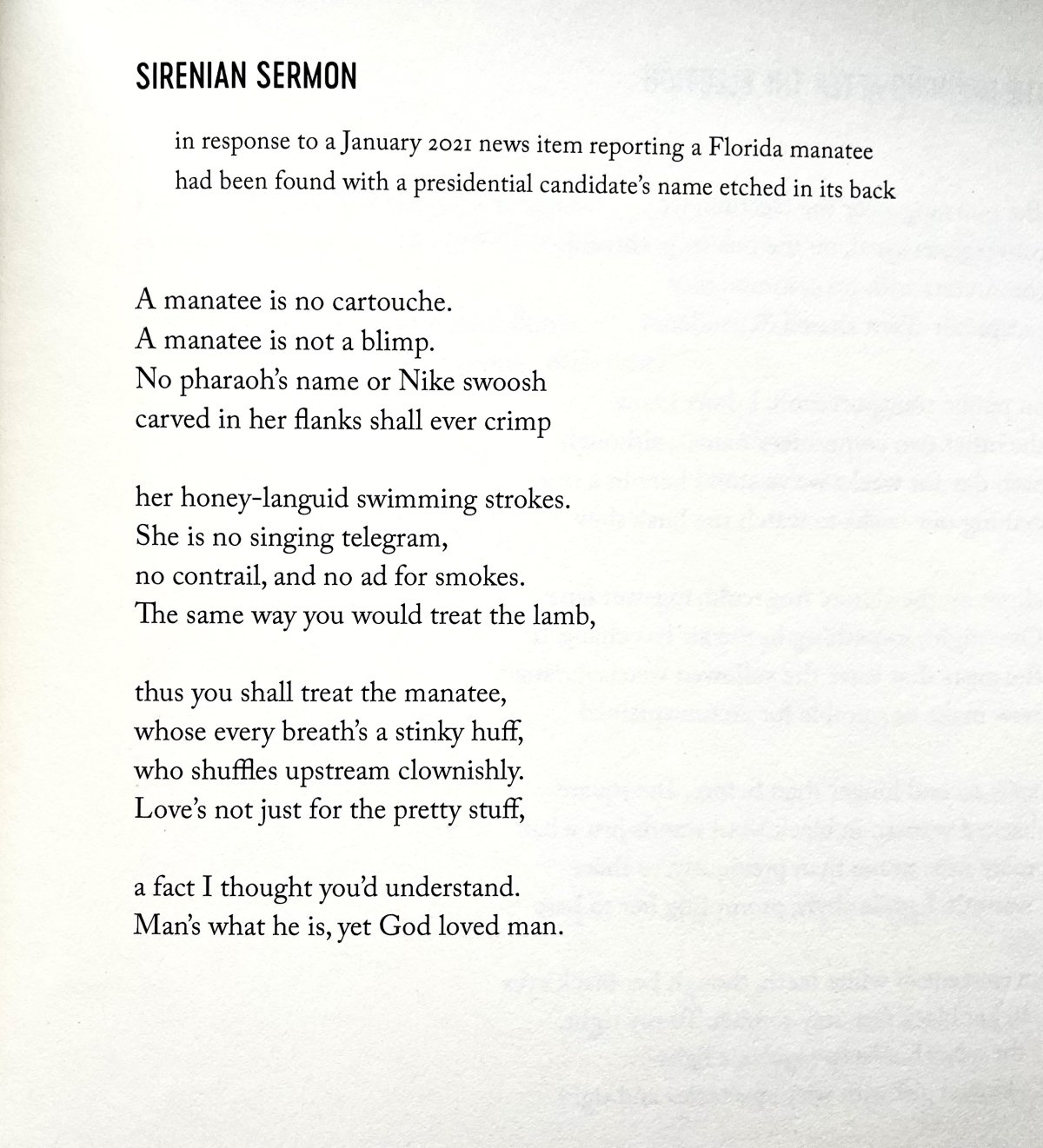

LA: I love how poems like “Sirenian Sermon” look at the political from intriguing angles—especially the manatee. Could you share a little about how the two became connected for you?

JL: One answer to this question is that I just have an obsessive temperament, and when I became obsessed with the manatee, I began to see everything through the lens of the manatee, and the stuff I was reading in the newspaper was no exception. But I think different people have different journeys that ultimately lead us all to realize how we are interconnected with nature. For people who grow up with pet animals like dogs and cats, this journey often begins with that one-on-one relationship between human and animal. For other people, the seed is something else: maybe a family camping trip in the wilderness that you went on as a child? For me, a major part of the journey has been this obsessive research and reading that I do about animals that fascinate me, like manatees. I think nature poetry will never lose its centrality, its potency, as long as poets stay honest about all the many ways we are interconnected with nature: how nature is not only some place of escape to be romanticized and pastoralized; human relationships with the environment have always been more complicated — and yes, more political — than that. Manatee starvation, human encroachment on manatee habitats — it’s ultimately impossible to talk about these kinds of things without talking politically.

LA: My day job is at The Cincinnati Review, and we’ve been running a blog series on Writers’ Day Jobs. I’d love to hear about your experience as a physician: how, if at all, does your day job inform—or relate to—your writing life?

JL: I do think being a radiologist has taught me to be better at seeing, just as my hobbies of drawing and painting are teaching me to be better at seeing. It’s given me a more grounded relationship to three-dimensional spaces, including the spaces inside the body. In a way, it’s been a great gift, to learn to see inside the body, to understand the body from all these wondrous angles. To always be seeking the connective tissue, the tendons and ligaments that put one bone at the beck and call of another. Left to my own devices, I might have become some sort of hermit, always floating off into my own mind, but working in medicine and medical education forces me to regularly step outside my comfort zone, to always be considering and re-considering how I exist as a self in relation to others. Also, I think constant exposure to medical jargon makes me hyperaware of how language can both clarify and obscure, anesthetize and waken. Then poetry becomes a deliberate choice: over and over, in writing a poem, one is choosing lucidity, wakefulness, clarity, illumination.